My blog has been dormant since early this year. During this period my husband went through four shoulder surgeries, and is now facing spine surgery. In a later post I’ll describe parts of all this which may be useful to others. But for now I am going to ease back into blogging with a short simple post.

As an older adult, I feel it’s not too often I do something for the first time ever. But Friday, while pursuing the sedentary pleasure of reading in the shade on our deck, I got to sit in the shade of trees I helped plant! And it felt good.

Over the years I have planted trees here and there, even sprouted acorns and popped them in the ground, knowing I would not be around to admire them when they got really big. I remember thinking once that I hoped someone somewhere was planting trees for me. Of course it’s true, “someone else” (including a host of squirrels, bluejays, and other animals which transport and hide seeds) has planted all the trees we gaze upon, eat the fruits of, and climb. But now, thanks to fast-growing seedlings from our two old birch trees, I sat in shade my husband and I had planted. It really did feel different, quite satisfying.

Birches make lots of little seeds which glide on the wind, sprouting wherever they encounter a moist spot. The slender trees now shading me started as little guys that I potted up to adorn the front deck; after a few years they outgrew their pots and were planted as a group. They’re prettier that way, and because the nature of birches, it takes several to make a sizable area of dappled shade.

We also have planted our own aspen grove, five that we bought in big pots, and they are doing well. Our hot dry summers and fast-draining soil (that’s a flattering term for it) aren’t ideal for either aspens or birch so I water them once or twice a week in the summer, and that seems to be enough.

I always marvel when I see houses without any trees: no shade, no windbreak, no fruit, none of the other comforts that trees offer us.

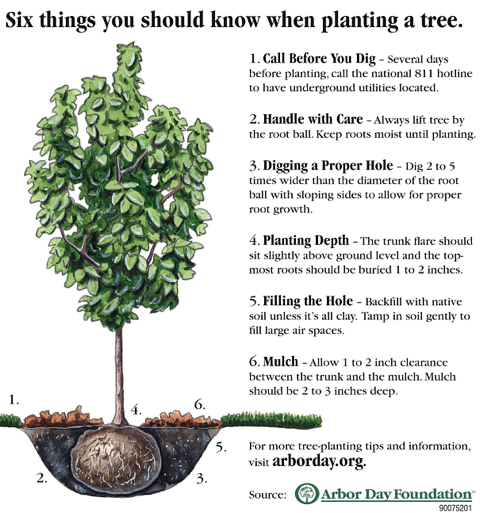

If your surroundings are lacking in trees, don’t wait for Arbor Day next spring. Plant some this fall and they’ll be ready to grow in spring. Get some advice on what does well in your region (use natives as much as you can) and what fits your needs with regard to questions such as year-round shade or not, growth rate & eventual size, likes to be in a lawn or not, species that provide food for birds or butterflies, blooms or fall color, amount of leaves and seeds to be raked if that is an issue, and so on.

Look for nursery sales as they pare back their holdings before winter; you can get some good deals. Or, just start your own. Some trees are pretty easy to grow though you’ll wait longer to sit in their shade, of course. Willow cuttings will grow readily if they get water; acorns can just be pushed into the ground and some will grow. There’s an inspiring short tale (The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono) about a shepherd who over many years revivified a desolate area by planting acorns each day as he followed his sheep. It’s fiction, but full of truth. Tree roots help stop erosion, their leaves cause the rain to fall more gently promoting absorption by the soil, their shade cools streams for wildlife and shelters other seedlings, their flowers, leaves, and seeds are food for many animals, and their presence gives birds, insects, and mammals places to live, breed, and hunt.

As Thomas Jefferson wrote, “I never before knew the full value of trees. My house is entirely embossomed [embosomed] in high plane-trees, with good grass below; and under them I breakfast, dine, write, read, and receive my company. What would I not give that the trees planted nearest round the house at Monticello were full grown. “ (in a letter to Martha Jefferson Randolph, July 7, 1793).

Two months before his death, at the age of eighty-three, he designed an arboretum for the University of Virginia. Such an epilogue to years of planting at Monticello was perhaps inspired by Jefferson’s own adage: “Too old to plant trees for my own gratification I shall do it for posterity.” (This and more about Jefferson and his tree-planting here; the aerial photo is of Monticello.)

To which I add: Leave the soil at the bottom (that will be beneath the root ball) undisturbed to avoid settling. If the tree is bare-root, gently spread out the roots over a cone of soil. Don’t stake unless really necessary, for instance when planting on a slope. Finally, water it in, and water regularly for the first couple of years or more depending on your weather. More tips here.