Here in wildfire country, it’s all about “defensible space” around your house, created by “fuel reduction.” We’re in the foothills of southern Oregon’s Siskiyou Mountains at about 2300 ft.; it’s dry, and rocky, and wildfires are a fact of life.

Shortly after we moved here I overheard someone say, at the local grocery store, “Plans for summer trips? No, we never go anywhere in the summer in case of wildfire.” This sounded pretty paranoid but I understand it better now that we’ve been here 12 years and seen two fires come close enough to worry about.

Pine-oak woodlands and mixed conifer stands seem to be the climax trees in our area, but 150 years of logging, farming, and road-building have caused a lot of disturbance. On our property, oaks, Douglas fir, and sun-loving Pacific madrones are the most common native trees. The madrones, which would be shaded out by dense mature forest, are often multi-trunked especially when resprouting after being cut; some of the oaks are the same. This results in brushy growths that can feed fire close to the ground. Shrubs like manzanita (Arctostaphylos sp.) and buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus) are very common and both are superb fuel for fires. We cleared one area ourselves, early on, of many pickup loads of buckbrush ranging to 5 feet tall. We burned them soon after cutting and even green they burned like gasoline.

Since that early effort of ours, the agencies concerned with fires and forests have gotten much more aggressive about fuel reduction on private as well as public lands. Small acreage homeowners like ourselves present a real problem to those fighting wildfires, since we expect our property, lives, and livestock to be protected and the fire-fighting resources–people, planes, equipment–are always stretched thin. Because we are part of the problem, we have been encouraged to be part of the solution as well by creating defensible zones around structures and along driveways, and having acreage “treated” to reduce fuel loads. In practice this means removing brush and dead trees, increasing distance between trees, and “limbing them up” by cutting branches that start below 6-10 feet.

The local fire district has a program to reimburse landowners for the costs of fuel reduction and we have participated in this twice. Someone comes out from the fire district to do a walk-around with you, discussing how fires travel and what changes you need to make, then you can either hire the work done or do it yourself, and upon a second inspection, be reimbursed on a per-acre basis for satisfactory completion. The amount is about $300/acre.

The financial aid means that it is possible for property owners to do fuel reduction even if they can’t do this strenuous job themselves. And when wildfires threaten private property, certified defensible properties will be given priority if there aren’t enough resources to protect everything.

Our first project was along the driveway and around the house. It included work we did ourselves (such as screening the open space between our large deck and the ground to prevent wind-blown sparks from igniting the dry wood from underneath) and work we paid for (the chain-saw removal of trees and brush and later burning of the brush piles).

This spring we heard the grants were available again and decided to have fuel reduction done on most of the rest of our 5 acres. This was a decision that we made with regret; the cleaned-up look, which some call a “parklike setting” of spaced-out trees with little growing between them, is not pleasing to our eye, provides less cover and food for wildlife, and will change the mix of wildflowers we enjoy. Twelve years of benign neglect has allowed the land to recover from various affronts and we’ve seen a significant increase in our favorite wildflower, the ephemeral Erythronium hendersonii (Henderson’s Fawn Lily, but we call it Trout Lily–both terms refer to the mottled leaves), and others.

However, thinking of our house becoming a pile of cinders was incentive enough. It is also true that big wildfires fed by abnormal accumulations of fuel are a long-term loss to wildlife here, where dry weather and poor soils make plant recovery slow; and both times we have chosen the more expensive method of selective hand-thinning by chainsaw over the cheaper way of clearing acres with whirling blades mounted on eco-buster caterpillar tractors. That method, as we saw when BLM used it next to (and actually on) our land, leaves a blasted wasteland that reminded me of photos of WWI France where months of artillery shelling turned forests into craters studded with splintered trunks rising at angles from the trampled mud.

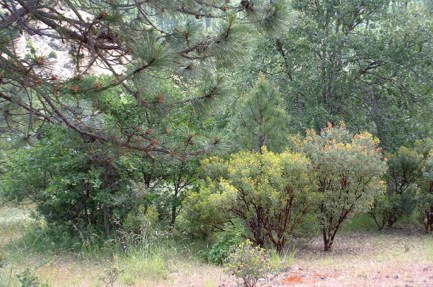

The latest clearing work has been completed, although warm weather arrived too soon for the piles to be burned; they’ll have to wait until the rains start in the fall. I didn’t think to take any “before” pictures, but for comparison the photo below is of an area untreated since we cut buckbrush a decade ago. It’s less dense than the treated areas were, before clearing, and has little madrone, but the growth of manzanita and oak clumps is similar.

The next photo is of a just-cleared section; the whitish band near the center is the driveway which would not have been visible at all before the thinning and limbing-up. The indistinct brown blob just to the left of the driveway (but closer) is a pile of branches and brush to be burned. A few piles will be left for the small creatures to shelter in, and a few large dead trees were left standing. The man who did the work is well experienced and at our request left a little extra brush where he thought the fire district would approve it.