As a chronic pain patient who took methadone for years, and experienced a lot of misunderstanding from medical professionals and laypersons about addiction, I greeted the House series with hope when I first saw it. It’s smart and interesting as tv goes, and Hugh Laurie is a fine actor who has done well with the unusual role. But beyond that, I thought having a chronic pain sufferer as a main character presented a great opportunity to break the stereotype that “taking pain meds longterm = addiction”. Dr. Gregory House is certainly well-informed about medical science as opposed to drug war hysteria, and no one can deny that he’s assertive!

Source unknown, appears only on generic odd picture sites. Found with Google image search.

House’s halo may fade as you read on.

However, the writers and producers are promoting the familiar hackneyed clichés about addiction–––worse, these clichés are false and are no longer accepted in current medical thought. And House, of all people, is represented as knowing no better, and accepting the label of “addict”.

Two of the doctors House works with (his boss Cuddy and his friend Wilson) say frequently that House’s professional and personal abilities are being damaged by his “addiction” (his everyday use of vicodin for constant severe pain in his leg), and this conflict has played out in many episodes in the first three years. [We never seem to watch the Fox channel, so we see House in reruns on other channels; if there has been a drastic change in the last season I wouldn’t know about it. But I doubt there’s been a change in a theme which has been used so often.]

I was moved to write this by seeing again the old episode titled “Detox” (episode 11, season 1, 2005). Cuddy challenges him to go a week without vicodin to “prove he’s not an addict”. House accepts the challenge, his prize being a month of no clinic duty, and he also accepts the premises: that if he shows signs of physical withdrawal it means he is addicted. He does show these signs, though he tries to hide or deny them, and he also suffers greatly increased pain. Feeling nauseated, he’s told that it’s withdrawal, and replies “No, I’m in pain. Pain causes nausea.” Maybe so, but withdrawal from opioids does too. Finally the pain and withdrawal symptoms make it impossible for him to function as his usual professional self: hyper-smart and intuitive diagnostician. A patient is depending on him, and so are his diagnosticians-in-training, and one of the latter gives him some vicodin and tells him to take it because he’s not able to do what needs to be done.

At the end, asked what he has learned, House says (close paraphrase): I’m an addict….But I’m not going to quit…I pay my bills, I work, I function.

His friend Wilson says, You’ve changed, you’re miserable and you’re afraid to face yourself…Everything’s the leg, nothing’s the pills?

House: They let me do my job, and they take away my pain.

So, House won’t abandon the vicodin because he cannot function without pain relief, but he caves to the notion that he is an addict.

There are so many things wrong with this, and the writers of a medical show ought to know better.

Addiction Versus Dependence

The refusal to distinguish between these two terms has cursed our management of pain for fifty years or more. But in the last couple of decades medicine has, at last, officially separated the two. Here is a discussion of the terminology from an authoritative source, a Consensus Document issued jointly by The American Academy of Pain Medicine, The American Pain Society and the American Society of Addiction Medicine, called Definitions Related to the

Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain. [I quote at length, so it will be clear that this represents exactly and completely the sense of this document. Emphasis is added.]

BACKGROUND

Clear terminology is necessary for effective communication regarding medical issues. Scientists, clinicians, regulators and the lay public use disparate definitions of terms related to addiction. These disparities contribute to a misunderstanding of the nature of addiction and the risk of addiction, especially in situations in which opioids are used, or are being considered for use, to manage pain. Confusion regarding the treatment of pain results in unnecessary suffering, economic burdens to society, and inappropriate adverse actions against patients and professionals.

Many medications, including opioids, play important roles in the treatment of pain. Opioids, however, often have their utilization limited by concerns regarding misuse, addiction and possible diversion for non-medical uses.

Many medications used in medical practice produce dependence, and some may lead to addiction in vulnerable individuals. The latter medications appear to stimulate brain reward mechanisms; these include opioids, sedatives, stimulants, anxiolytics, some muscle relaxants, and cannabinoids.

Physical dependence, tolerance and addiction are discrete and different phenomena that are often confused. Since their clinical implications and management differ markedly, it is important that uniform definitions, based on current scientific and clinical understanding, be established in order to promote better care of patients with pain and other conditions where the use of dependence-producing drugs is appropriate, and to encourage appropriate regulatory policies and enforcement strategies.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), and the American Pain Society (APS) recognize the following definitions and recommend their use:

ADDICTION

Addiction is a primary, chronic, neurobiologicneurobiological disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

PHYSICAL DEPENDENCE

Physical dependence is a state of adaptation that often includes tolerance and is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist…

TOLERANCE

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

DISCUSSION

Most specialists in pain medicine and addiction medicine agree that patients treated with prolonged opioid therapy usually do develop physical dependence and sometimes develop tolerance, but do not usually develop addictive disorders. However, the actual risk is not known and probably varies with genetic predisposition, among other factors. Addiction, unlike tolerance and physical dependence, is not a predictable drug effect, but represents an idiosyncratic adverse reaction in biologically and psychosocially vulnerable individuals. Most exposures to drugs that can stimulate the brain’s reward center do not produce addiction. Addiction is a primary chronic disease and exposure to drugs is only one of the etiologic factors in its development.

Addiction in the course of opioid therapy of pain can best be assessed after the pain has been brought under adequate control, though this is not always possible. Addiction is recognized by the observation of one or more of its characteristic features: impaired control, craving and compulsive use, and continued use despite negative physical, mental and/or social consequences. An individual’s behaviors that may suggest addiction sometimes are simply a reflection of unrelieved pain or other problems unrelated to addiction. Therefore, good clinical judgment must be used in determining whether the pattern of behaviors signals the presence of addiction or reflects a different issue.

Behaviors suggestive of addiction may include: inability to take medications according to an agreed upon schedule, taking multiple doses together, frequent reports of lost or stolen prescriptions, doctor shopping, isolation from family and friends and/or use of non-prescribed psychoactive drugs in addition to prescribed medications. Other behaviors which may raise concern are the use of analgesic medications for other than analgesic effects, such as sedation, an increase in energy, a decrease in anxiety, or intoxication; non-compliance with recommended non-opioid treatments or evaluations; insistence on rapid-onset formulations/routes of administration; or reports of no relief whatsoever by any non-opioid treatments.

Adverse consequences of addictive use of medications may include persistent sedation or intoxication due to overuse; increasing functional impairment and other medical complications; psychological manifestations such as irritability, apathy, anxiety or depression; or adverse legal, economic or social consequences. Common and expected side effects of the medications, such as constipation or sedation due to use of prescribed doses, are not viewed as adverse consequences in this context. It should be emphasized that no single event is diagnostic of addictive disorder. Rather, the diagnosis is made in response to a pattern of behavior that usually becomes obvious over time.

Pseudoaddiction is a term which has been used to describe patient behaviors that may occur when pain is undertreated. Patients with unrelieved pain may become focused on obtaining medications, may “clock watch,” and may otherwise seem inappropriately “drug seeking.” Even such behaviors as illicit drug use and deception can occur in the patient’s efforts to obtain relief. Pseudoaddiction can be distinguished from true addiction in that the behaviors resolve when pain is effectively treated.

Physical dependence on and tolerance to prescribed drugs do not constitute sufficient evidence of psychoactive substance use disorder or addiction. They are normal responses that often occur with the persistent use of certain medications. Physical dependence may develop with chronic use of many classes of medications. These include beta blockers, alpha-2 adrenergic agents, corticosteroids, antidepressants and other medications that are not associated with addictive disorders.

How important are definitions?

Few things are more important. We interact with the world through language. Words cause emotional reactions, compose our thoughts, represent us to others. Would you want to be introduced to a group of strangers as an “addict” or as a “pain patient”?

Let’s look at the decision to replace “addiction” with “dependence” in the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). This thick volume is the official dictionary and guide for defining mental disorders, including addictive behaviors. (Change in the DSM can contribute to profound social and legal change––as when, after a series of redefinitions, homosexuality was finally removed from the list of disorders in 1987.) An editorial in the American Journal of Psychiatry (2006) discusses this decision to use “dependence” not only to describe physical dependence, but also for addiction, as differentiated in the document quoted above.

All of the authors of this editorial are involved in the next revision of the DSM (DSM-V), and one has been part of the revisions since the 1980’s. They favor changing back to a distinction between “addiction” and “dependence,” and describe how the decision was made to merge both into “dependence”:

Those who favored the term “dependence” felt that this was a more neutral term that could easily apply to all drugs, including alcohol and nicotine. The committee members argued that the word “addiction” was a pejorative term that would add to the stigmatization of people with substance use disorders. A vote was taken at one of the last meetings of the committee, and the word “dependence” won over “addiction” by a single vote.

It was a victory for Political Correctness!

The authors criticize the widening of the term because of the negative effect on pain patients:

This [redefinition] has resulted in confusion among clinicians regarding the difference between “dependence” in a DSM sense, which is really “addiction,” and “dependence” as a normal physiological adaptation to repeated dosing of a medication. The result is that clinicians who see evidence of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms assume that this means addiction, and patients requiring additional pain medication are made to suffer. Similarly, pain patients in need of opiate medications may forgo proper treatment because of the fear of dependence, which is self-limiting by equating it with addiction.

A Canadian article (2006) describes the reluctance of many physicians to prescribe opioids for pain, and why they are reluctant:

In a recent national survey, 35% of Canadian family physicians reported that they would never prescribe opioids for moderate-to-severe chronic pain, and 37% identified addiction as a major barrier to prescribing opioids. This attitude leads to undertreatment and unnecessary suffering.

This is over one-third of Canada’s doctors who will never “prescribe opioids for moderate-to-severe chronic pain” no matter what. We cannot know how many would do the ethical thing and refer such patients to someone more experienced in treating pain, and how many just leave the patients to their own devices. If 35% would never prescribe opioids, some additional percentage would fall into the “rarely” category, which also results in undertreatment of pain.

Why does medical opinion on a fictional TV show matter?

Current medical “best practices” and principles regarding the differentiation of addiction from dependence have been slow to reach doctors and other medical professionals, let alone the public. Of course doctors should not be getting their medical information and attitudes from television, but television has a strong influence on viewers who know little about the topic presented–that’s all of us who are not medically trained. A person who believes that taking opioids results in addiction is far less likely to push for adequate pain treatment for him/herself, or family, and may even reject it if offered. If friends, relatives, and employers of pain patients share the confusion about addiction, they will exercise social pressure or threaten loss of employment. So the attitudes promoted by a popular TV show––in the US, House was the most-watched scripted program on TV during the 2007–08 television season––can have profound effects on the health care people receive.

When House stops taking the vicodin, he suffers headaches, sleeplessness, nausea, inability to concentrate, and irritability. All are symptoms of physical dependence, as in the definition paper cited above. That these same symptoms are felt by addicts is beside the point: addicts and chronic pain patients both are physically dependent, and both will suffer similar withdrawal symptoms as a result. For the pain sufferer, the symptoms of increased pain are added.

As a pain patient, I have experienced withdrawal from methadone. It is hell. It gave me much more compassion for addicts. Yet, in trying to get off methadone “cold turkey” when my doctors claimed they could not assist me, I went through seven days and nights of absolutely no sleep, intense physical and mental suffering from the withdrawal, and increased pain. There’s the pain you were medicating, and in addition the cessation of methadone makes all your bones ache, worse than any flu. And all this time the methadone was on the shelf. Untouched. Not typical addict behavior. On the eighth day with no sleep I realized that there had been no lessening of my symptoms, and that I could not endure it another 24 hours, so with distaste and reluctance I began taking the methadone again. I resolved then that I needed to find different doctors, who would help me through this, and subsequently did so with complete success. (I wrote about this in an earlier post.)

In my case the pain being treated had changed (improved, by a nerve block) during my time on opioids; the increased pain I had during withdrawal was nothing like that which House suffered from his leg. He showed great fortitude and self-control, but while dramatic it was medically pointless. The man has pain so bad he cannot function if it is not controlled; if nothing else works other than opioids, then that’s what he needs to use. Current medical thought recognizes this; the writers of the show do not.

Some of the behaviors relative to pain medication shown by House are reprehensible, such as stealing medication and forging prescriptions. This seems like classic drug addict behavior. But see the paragraph above on Pseudoaddiction, including the statement “Even such behaviors as illicit drug use and deception can occur in the patient’s efforts to obtain relief. Pseudoaddiction can be distinguished from true addiction in that the behaviors resolve when pain is effectively treated.” In fact, much of House’s often-criticized behavior has to be considered in light of the fact that even the vicodin never adequately relieves his leg pain. Irritability, mental and physical restlessness, combativeness, and harsh remarks can be the signs of unrelieved physical pain.

Chart from “Pain Assessment in Older Adults” (2006). The source references mentioned at the bottom of the chart are : 8. The management of persistent pain in older persons. American Geriatric Society (AGS) panel on persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:S205-S224; and 9. Ferrell BA, Chodosh J. Pain management. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, et al. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 2003:303-321.

We have been told that even before his leg injury, House wasn’t a sunny sociable person. But he’s gotten worse since then, and in the show the doctors around House nearly always blame his pills––his addiction–not his pain.

Addicts and pain patients, differences and similarities

I intended to include some data here about the low actual rate of addiction (not dependency) in pain patients as a result of taking pain meds. I remember reading figures that ranged from 5% to 10%. When I did a quick search for substantiation I found that many of the research articles online are only available for a fee. The rates I did see varied so much, I must assume that the studies are not all using the same standards. Different researchers have different definitions of addiction vs. dependence; there is also an overlap of characteristics or symptoms between addicts and those who are physically dependent. If I had had no legal access to relief when I was in extremis after seven days of no methadone, I probably would have lied or stolen, if necessary to end the withdrawal. Nothing violent; I would have gotten myself somehow to the emergency room instead. But if turned away there, who knows?

This is the sort of mental and physical suffering that confronts the organism with a stark choice: solve this, or die. (If you are too debilitated to protect yourself or find food, you will die, as far as the primitive part of our brain is concerned.) Once physical dependency has been established, both addicts and pain patients are motivated to get their drugs, driven more powerfully than anyone can imagine who has not experienced it. The distinctions between addict and dependent patient must be made on criteria other than the evidence of physical dependence, since this is the same for both.

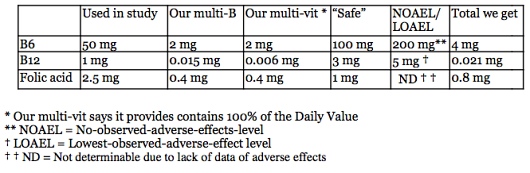

The chart below presents some criteria that seem to square with my experience and reading, although the source does not give scholarly or research citations for it.

[The last item under Addicts should read “The life of an addict is a continuous downward spiral.”]

Individual responses to potentially addictive drugs vary. Not everyone who tries heroin becomes addicted. Different responses are based on biological and psychological factors we are only beginning to glimpse: everything’s neurological in the end, I suppose, but increasingly it appears that experience (from conditions in utero to nutrition, upbringing, and exercise) can cause physical changes in the brain and nervous system, and therefore in thinking, emotion, and behavior [see note 1]. Even the physical brain, where our sense of “I” resides, is changeable throughout our lives: adapting, adding complexity, growing (or shrinking) based on what happens to us. The activity of our genes themselves can be enhanced, reduced, suppressed entirely, depending on outside conditions from before birth to the day we die.

How should society regard people with chronic pain?

When a starving person steals bread, we do not say that he should have simply endured his hunger, or that he is “addicted” to food. Believe me, the situation of a person in great pain, or even moderate chronic pain, is also desperate and unbearable, and the organism will get relief.

The compassionate and socially responsible action is to meet these needs in an appropriate way. Can we assist this starving person in earning money so as to feed himself or herself? If not, most of us agree that the helpless, the elderly, the people so injured by life as to be unemployable, should receive aid rather than be allowed to starve or freeze to death. The pain patient deserves the same action: the question to be asked is: How can the pain best be alleviated? There may be surgical options, transfer to a different job, physical therapy, use of TENS units and the like, as appropriate. Meditation, mild exercise, and cognitive training may offer some relief too. But the response to pain must not be limited to only non-drug approaches.

The patient is the final judge of what works, and how much pain is too much, and the patient should not be silenced with threats and accusations of addiction.

A question that needs to be asked about drug addiction is Why? Why do so many of our fellow citizens seek out heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, illegal prescription drugs, too much alcohol? What is their pain? Not physical, perhaps, but certainly psychological or spiritual: despair, lack of meaning in life, lack of true positive connexion to other human beings and to the natural world. Until we approach drug addiction in this way we will never understand how to reduce its occurrence. Neither after-the-fact tactics (punishment, ostracism, rehab), nor prevention (education and interdiction) have worked very well. But asking Why? about addiction would reveal aspects of our society that are senseless and cruel to many, but pleasant and profitable for a few. Danger, ssssshh!

We have been so cowed and brainwashed by the continually failing War on Drugs and our native streak of puritanism that we even permit medical professionals to deny adequate pain relief to terminal cancer patients. Is it really because they “might get addicted” in the weeks before they die? Or is it the imposition of society’s fears and prejudices upon the most helpless among us? Clearly, we have made little progress in reducing the numbers of illegal drug users over the past forty years––but law-abiding people who go to doctors, they can be denied and controlled.

And so, apparently, can Dr. Gregory House, who is pitched to us as the independent thinker extraordinaire, smart and brave, ready to track truth to its lair and drag it out into the daylight. I wish his writers would let him do exactly that on the issue of pain and addiction.

1. Further reading on the “plasticity” of the brain (an unsystematic quick gathering)

- Scientists map maturation of the human brain (2003), a short overview

- Brain changes significantly after age 18 (2006), “The brain of an 18-year-old college freshman is still far from resembling the brain of someone in their mid-twenties. When do we reach adulthood? It might be much later than we traditionally think.”

- Research finding persistent physical and functional changes in human brains caused by smoking, chemotherapy,

- Empirical research on structural brain changes affecting social cognitive development after childhood (2007);

- Various environmental factors can cause “epigenetic changes…reversible heritable changes in the functioning of a gene can occur without any alterations to the DNA sequence. These changes may be induced spontaneously, in response to environmental factors…” and be associated with development of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders or the quality of an individual’s performance as a parent

- Childhood lead exposure can predict criminality(2008), even after controlling for factors such as socioeconomic status of the family; “Lead can interfere with the brain by impairing synapse formation and disrupting neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin. It also appears to permanently alter brain structure.”