Today I’ll start with a genus of plants that is a bit different: it’s a “living fossil” from the Devonian (405 million to 345 million years ago, age of fishes and appearance of amphibians) when some specimens topped 90 feet (30 meters), it does not flower, and it’s found on every continent except Australia and Antarctica. And, people both cook it and use it to scour pots. This is the genus Equisetum, commonly called horsetail. It’s a lover of wet places and we found it at the edge of a creek.

Above are both stages of growth side by side: the jointed stem somewhat like bamboo, which I plucked from a slope next to the creek, and a smaller stem that has already “leafed out” in radial whorls of needle-like leaves. This picture from Wikipedia shows the leaf whorls well.

The unleafed stems were beautifully colored,

and hollow.

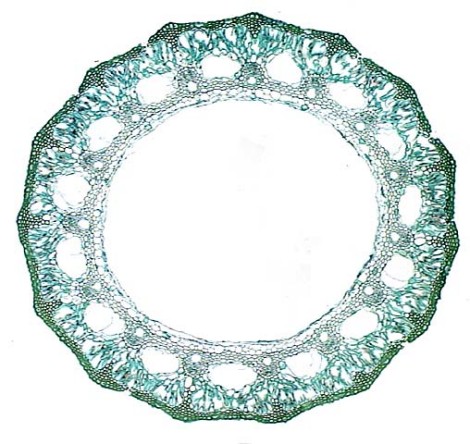

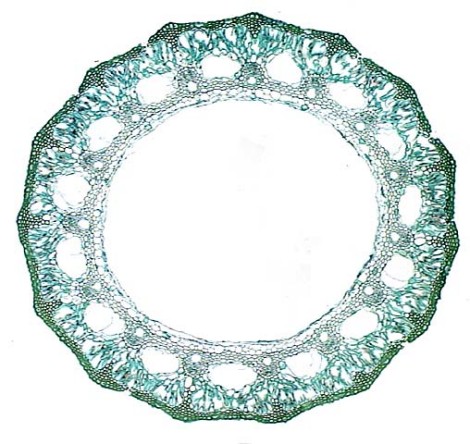

The stems are said to be “anatomically […] unique among plants”.

This beautiful microphotograph is of a stained cross-section of stem.

Equisetum species grow from underground rhizomes that are extremely persistent and invasive; think twice before deciding it is the perfect plant for that boggy spot in your yard, because it is likely to be there (and maybe other places too) forever. They’ve been used for all sorts of purposes through history. Many a camper and wildland dweller has scoured pots with the stems, which have a lot of silica in them, and they are “still boiled and then dried in Japan, to be used for the final polishing process on woodcraft to produce a smoother finish than any sandpaper.” The leaves are used as a dye for a soft green color. The young shoots are eaten but require special treatment because they contain the enzyme thiaminase[172], a substance that can rob the body of the vitamin B complex.

In addition to spreading locally via rhizomes, Equisetum produces spores on terminal cones, shown below.

Photo source.

There are several species found in Oregon, and I think the one we saw and photographed is Equisetum hyemale but I’m not sure. Equisetum, by the way, means “horse-bristle”, as in “scrub-brush”, and hyemale is from hiemis, “winter” (both terms from the Latin). Other common names include scouring rush, pipes (children play with them, as the hollow segments can be taken apart and put back together), and scrub grass.

Downstream from the equisetum, back on the road, we saw next to the narrow concrete bridge a small tree growing in the water

and laden with tresses of white blooms.

This is choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), a species of “bird cherry”. Fruits are small and sour but very high in antioxidant pigment compounds, like anthocyanins. With a lot of added sugar, they are used to make wines, syrups, jellies, and jams.

Yarrow cultivars are familiar garden plants. Here is the ancestor of those, Achillea millefolium or common yarrow. It’s found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, even in the Himalayas.

A closer view of the flowers.

The leaves are distinctive, giving rise to the common name plumajillo, or “little feather” in Spanish-speaking New Mexico and southern Colorado, and to the millefolium (thousand-leaf) in its scientific name.

It’s called Achillea after Achilles, Homer’s hero in the Iliad, who was well-trained in healing wounds as well as in causing them. Yarrow has been used for thousands of years to staunch the flow of blood and for other medical purposes, and among its common names are “herbal militaris” or soldier’s herb, nosebleed plant, and soldier’s woundwort. But there doesn’t seem to be any peer-reviewed research into compounds in the plant that may have medicinal properties. One site I visited, planetbotanic.ca, promoted it as an immune stimulant to ward off colds. But then the site’s “fact sheet” also tells us that “Yarrow’s scientific name hints of a legendary use. Achilles’ famous heel is said to have been healed when yarrow was applied to it.” Other than the words “Achilles” and “heel”, everything in this sentence is wrong: Achilles’s mother held her infant by the heel while dipping him in the River Styx to confer invincibility upon him. The water did not touch that part of his body, and eventually the warrior who had survived many wounds was killed by an arrow to the heel, from the bow of Paris.

Achilles bandaging the wounded Patroclus. From a Greek vase painting. Source.

Paris was not much of a fighter. He mostly stayed with the women and old men observing the ten years’ war from the heights of Troy’s great battlements, so it’s ironic that his blow (even if delivered from a distance) should kill the otherwise invincible champion of combat, Achilles.

Achilles in battle. Source.

Homer doesn’t include the death of Achilles in the Iliad; he ends with a final consequence of Achilles’s wounded pride, fit of rage and refusal to fight, when his friend Patroclus goes out wearing the great warrior’s armor to drive back the attacking Trojans. Patroclus and the Greeks carried the day, indeed seemed about to breach the walls of Troy, but the god Apollo intervened, striking Patroclus so as to daze him, sending his borrowed helmet spinning in the dust; one Trojan wounded him from behind and then Hector, Prince of Troy, delivered the fatal blow. When word of this reached Achilles he put aside his pride under force of a greater rage, and went after Hector like a lioness whose cub’s been killed.

All is not the clashing of bronze and shedding of blood in the Iliad. This is a famously tender moment, famously sad as well, one that is familiar to too many soldier parents.

“And tall Hector nodded, his helmet flashing:

… shining Hector reached down for his son—but the boy recoiled,

… screaming out at the sight of his own father,

terrified by the flashing bronze, the horsehair crest,

the great ridge of the helmet nodding, bristling terror—

so it struck his eyes. And his loving father laughed,

his mother laughed as well, and glorious Hector,

quickly lifting the helmet from his head,

set it down on the ground, fiery in the sunlight,

and raising his son he kissed him, tossed him in his arms…”

Iliad Bk. 6: 556-56, in the very readable translation by Robert Fagles. Source.

The Iliad ends with Hector’s father King Priam of Troy humbly seeking his son’s body for burial. In his boundless desire for vengeance upon his friend’s killer, Achilles has been dragging the body behind his chariot, around and around the city. Yet when the old man, escorted through the enemy lines by a disguised Mercury, kneels before Achilles, kisses his hands, and implores his son’s killer to think of his own faraway father and give up Hector’s body, Achilles weeps with Priam, and relents.

All that was about 1250 BC, yet reading the Iliad we find characters and feelings that match those we can see around us still. The immense destructive power of rage and wounded pride are as great now as then. And the history of the humble yarrow also connects us to people like Achilles and Hector; their eyes saw these flowers, crushed these leaves to keep with them against the likelihood of wound from sword or spear.

Troy, level VI, defensive walls, as excavated by Schliemann. This level is about a hundred years earlier than that believed to have been the city destroyed by war in the Iliad, about 1250 BC. Source.